"Too much protein is as bad as smoking."

"Meat and cheese cause early death."

"High-protein diet linked to aging, cancer, and diabetes."

"Now we can't eat protein. What can we eat?"

If you've been able to avoid the barrage of headlines like this that have seemingly taken over the Internet in the last week, consider yourself lucky. It never ceases to amaze me how one single study, once it's attached to a memorable hook, can seem like breaking news that every outlet in the world needs to cover without the slightest bit of scrutiny.

Now every time you order a double chicken breast with veggies on the side, you run the risk of receiving a snide remark about how all that protein you eat is going to kill you.

Many of you have asked me through social media about my take on the study that provoked these stories, and you'd better believe I have one. Read on for some ammo to fire back at your friends and family as they butter their fifth piece of white bread to go with their pasta dinner.

Running the Numbers

The study that everyone is talking about is an epidemiological study from the University of Southern California. An epidemiological study means that they did not actually perform a study in a lab, but simply looked at factors in life to make associations or correlations.

The researchers did some further research in mice and yeast to support their hypothesis, but that is a far leap to connect to humans. So I will focus solely on the epidemiological study in humans.

In this particular study, the researchers took data from a pre-existing survey known as NHANES III, one of the largest national surveys of health and nutrition done in the United States, assessing about 6,300 people over the age of 50 years old. The authors of the original study collected a wide range of data about their subjects and followed them for 18 years, even analyzing their death rates and cause of death.

Armed with this raw data, the authors of the new study separated the subjects into three different groups:

- High protein: People who consumed 20 percent or more of their daily calories from protein.

- Low protein: People who consumed 10 percent or less of their daily calories from protein.

- A middle group between the low and high groups.

They reported that, among subjects aged 50-65, people who consumed a high-protein diet, mainly from animal protein, were 75 percent more likely to have died over the next 18 years than people consuming a low-protein diet. These unfortunate individuals also had a fourfold greater risk of dying from cancer, as well as a greater risk of dying from diabetes.

On the other hand, in people 65 and older, there was no greater risk of death or death from cancer from eating a high-protein diet. In fact, it seemed that the higher-protein diet in people over 65 decreased the risk of overall death and death from cancer while the low-protein diet increased their risk of death.

However, there was still a greater risk of dying from diabetes in all ages eating a higher-protein diet.

A Logical Leap

Armed with this data, the scientists leapt to the conclusion that anyone age 50-65 should consume a very low-protein diet, where protein represents as low as 10 percent of total daily calories or less. If you consumed 3,000 calories per day, that would equate to 75 grams of protein total per day. If you were down at 2,000 calories per day, that would be just 50 grams!

On the other hand, researchers also suggested that people over the age of 65 should consume a high-protein diet, since there is a relationship between higher protein intake and reduced death rates in older people. That's right: little to no protein for 15 years, and then you should suddenly go back on a high-protein diet at age 65. This, researchers suggest, will prevent muscle loss, frailty with aging, and death.

If the study were the extent of what the researchers said, perhaps the article you're reading wouldn't even be necessary. However, the lead researcher, Dr. Valter Longo, went on to state in a much-quoted interview afterward that eating a higher-protein diet is as bad for middle-aged people's health as smoking cigarettes.

That quotable statement has helped fuel the hundreds of stories about this story, and it makes a rebuttal necessary. Luckily, it's not difficult to do.

One Day Is Not A Diet

There are a number of serious flaws with this study, but the fatal flaw was how the researchers determined the subjects' protein intake. It was with a method called "24-hour recall." Basically, the subjects were asked what they ate the prior day. Yes, just one day!

It's absolutely ridiculous to think that what these people ate in one random 24-hour period of their life is representative of the diet they maintained for up to 18 years, or 6,570 days. This is to say nothing of the likelihood that people age 50 or above can't recall with perfect accuracy what they ate for breakfast today, let alone what they ate yesterday. We honestly have no idea what the subjects' diets were like over the 18 years that they were followed.

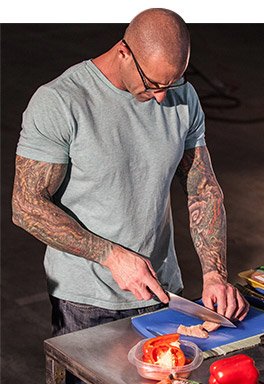

Another problem was that the researchers only calculated total protein from "animal sources" or "plant sources." There was no mention of the source of the animal protein, nor what else anyone was eating with it. Was the animal protein from leans cut of beef, poultry, dairy, and eggs along with a low- to moderate-carb diet that was rich in vegetables? Or was the protein from burgers eaten on buns with fries, fried chicken with mashed potatoes, and salami sandwiches on white bread with mayo?

The NHANES III interviews were performed in the late 1990s on subjects who were born in the 1940s and earlier. Given what we know about the dietary habits of families during the early part of the 20th century, I'm inclined to believe that that most of the diets fell into the latter camp. Not that it even matters, since it's just one day among thousands.

The researchers also concluded from the stats that carbohydrate intake had no impact on overall death rates, nor on death from cancer and diabetes. But protein intake did have a negative impact on diabetes. I'm expected to believe that eating chicken breasts, lean beef, fish, eggs, and low-fat dairy has a negative impact on diabetes, but eating a loaf of white bread doesn't? Sorry, not buying it.

I can point to a stack of trustworthy studies which say that one of the best dietary methods for people with diabetes is to follow a higher-protein, lower-carb diet. In fact, there is evidence that simply dropping back on carb intake can reverse type-II diabetes.

Need one more reason to reject the 24-hour dietary recall method? It says nothing about the level of physical activity or exercise habits of the 6,000-plus people. Even if they were consistently eating a higher-protein diet, I can almost guarantee you that those people who trained and lived a healthy lifestyle would have a lower incidence of overall death, death from cancer, and especially death from diabetes.

Silly Advice

The study itself may be flawed, but the dietary recommendations that accompany it are some of the silliest advice I've heard in quite a while.

If it seems bizarrely arbitrary that a 64-year-old isn't allowed any protein, but a 66-year-old gets plenty of it, you're right. Setting that aside: If you eat barely any protein for 15 years between the ages of 50 and 65, it will be far too late to suddenly start pounding protein again when you are 66 years old. You will have already lost significant muscle mass, which has been shown to decrease both quality of life and lifespan in senior citizens. A sudden blast of protein at that point could be a case of too little, too late.

One thing I haven't mentioned so far is that higher-protein intake and higher risk of death from cancer in the study was associated with higher insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) levels in the subjects. The relationship between IGF-I and cancer progression, as well as high-protein intake and IGF-I, is interesting. But we are far from having a true handle on cancer, its progression, and death resulting from it.

There are far too many dietary interactions going on to call out one macronutrient as the scapegoat. There are genetic factors, epigenetic (gene expression) factors, and environmental factors that we are far from understanding, and for the researchers to make sweeping nutrition rules at this point is simply premature.

As much as we would like to get closer to understanding cancer, the truth is that the more we learn, the more we still need to learn. Hinging matters of life and death on any single villain, be it a macronutrient or a protein like IGF-1, is overly simplistic. But for the lead researcher to top it off with a comparison to smoking is downright irresponsible.

Jim's take-home points

Should you be concerned about eating a high-protein diet? No! Should you switch to a low-protein diet when you turn 50 and wait to switch back to a high-protein diet after you reach 66? No! The data from this study, and the conclusions that the researchers made, are packed with as many holes as the Swiss cheese they tell us we shouldn't be eating.

Setting aside what we don't yet know about IGF-1 and cancer, let's think of it purely in terms of the power of the argument. Is a single day in a stranger's life enough to convince you to eat a total of 50-75 grams of protein per day, be weak, and potentially have a poor quality of life, simply to obey some watery theory pushed by a few scientists? Of course not!

Live your life strong and healthy. Do what you have always known to be good for you, and what makes you feel good: Eat protein!

Reference

- Levine, M. E., et al. Low Protein Intake Is Associated with a Major Reduction in IGF-1, Cancer, and Overall Mortality in the 65 and Younger but Not Older Population. Cell Metabolism, 19(3): 407-417, 2014.