If you want to build muscle, you have to train hard—no argument there. But how does hitting the gym actually translate to an increase in muscle growth? It is now well appreciated that the intramuscular signaling pathway, known as the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex, is required for promoting gains in muscle.[1] Every time you hit the gym, you trigger the mTOR signaling pathway, which, in turn, allows for a robust increase in muscle protein synthesis.

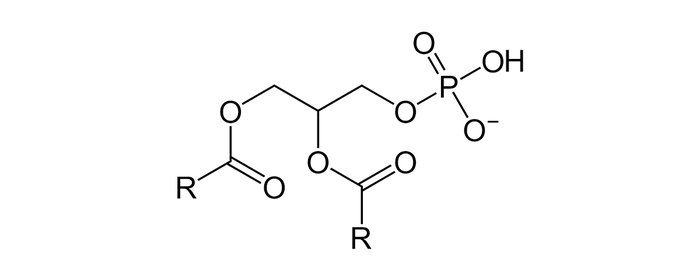

Despite decades of research investigating this phenomenon, the exact mechanisms underlying muscle growth are not fully understood. However, phosphatidic acid (which we will refer to as PA for this article) has been shown to play an important role in this process.[2] And when that became clear, it wasn't long before PA supplements started showing up on the market.

So, is there science to back this supplement? Let's dig in and find out.

What is phosphatidic acid?

PA is a unique lipid molecule that acts as a direct regulator of mTOR signaling. In other words, PA effectively "turns on" muscle protein synthesis in response to resistance exercise. Given the apparent role of PA in mTOR activation, researchers have started to question whether simply increasing the amount of PA in the diet would exert a favorable impact on muscle growth and strength.

It is noteworthy to mention that PA can be found naturally in the diet, but only in extremely small quantities. PA is found in the largest quantities in vegetables such as cabbage, which contain 0.5 milligrams per gram.[3]

However, the small amounts found in the diet are negligible compared to the 250-750 milligram doses of PA administered in research studies.

What does the research say?

Can we effectively increase muscle protein synthesis by supplementing with PA? In a laboratory setting, PA has shown to increase mTOR signaling in isolated muscle cells.[4-6] Additionally, in a study done with rats, PA and whey protein sparked an increase in muscle protein synthesis. However, using them together actually blunted the anabolic effect of whey protein, indicating that there may be an interference effect rather than a synergistic effect on muscle-building.[7]

Surprisingly, researchers have not yet investigated whether a supplemental dose of PA actually increases mTOR activation or muscle protein synthesis in humans. Additionally, in order for PA to elicit an anabolic effect on muscle, the orally supplemented dose would need to be absorbed into the blood stream and taken up by the muscle.

These variables have also not yet been investigated. Therefore, the extent at which PA reaches the muscles and is absorbed by the muscle cells to elicit an effect following oral supplementation is currently unknown.

Is there a physique or performance application?

To date, there have been five research studies investigating the potential effects of PA supplementation in trained men. Unfortunately, the findings are mixed and require some interpretation.

The first pilot study was conducted in 2012 in which 16 resistance-trained men were randomly assigned to consume either 750 milligrams of PA daily or a placebo, during eight weeks of unsupervised training.[8] PA supplementation showed to have a likely, but not statistically significant, benefit on measures of hypertrophy and strength—basically, the equivalent of saying "eh, maybe there's something going on here." These preliminary findings were intriguing to say the least, and sparked some interest into this potential muscle-building supplement.

Another study employed a similar research design whereby 28 resistance-trained men were randomly assigned to consume 750 milligrams of PA daily or a placebo during an eight-week training program.[5] In this study, no significant differences were observed for bench-press strength. However, the PA group added more weight to their leg-press max and gained a significantly greater amount of lean body mass. In particular, they had a greater increase in leg muscle size.

Using a similar training design, a different study also showed that PA supplementation produced greater gains in measures of hypertrophy and strength.[9] However, the 750 milligram dose of PA was provided as part of a multi-ingredient supplement that contained other muscle-building agents including leucine, HMB, and Vitamin D3. Therefore, it remains unclear to what extent, if any, PA affected the results of this study. The addition of other ergogenic ingredients confounds the ability to draw conclusions on PA supplementation in isolation.

To investigate different doses of PA, a research team conducted an eight-week training study in 28 resistance-trained men; however, in this case, participants were randomly assigned to receive 250 milligrams of PA, 375 milligrams of PA, or a placebo daily.[10] Similar to the pilot study, no significant differences were found between groups for muscle size or strength after the supplementation period. However, likely positive effects were reported for some measures of muscle size and strength using an unconventional statistical procedure.

Most recently, my lab investigated the effects of PA supplementation on muscle thickness and strength following an eight-week weight-training program in 15 resistance-trained men.[11] We found that a daily dose of 750 milligrams of PA did not offer any benefit for increasing muscle size or maximal strength, compared to a placebo group.

The bottom line, for now

A considerable amount of research shows that PA is involved in the regulation of mTOR signaling, the master switch of muscle growth. The small number of well-controlled experimental research studies suggests that PA supplementation might be a useful dietary strategy to increase muscle size and strength during a relatively short and intense training period, like eight-weeks.

However, it's worth noting that only one study has reported statistically significant effects of PA supplementation in isolation on muscular adaptation. Unfortunately, the current research findings are rather equivocal and it is difficult to answer whether PA supplementation would provide a competitive edge, or if it would be any more effective than just consuming lecithin and choline, both of which supply some PA, but also other phospholipids involved in the synthesis of PA in the body.[12]

More research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of this muscle-building supplement before I would recommend it as a staple in your supplement stack. Finally, research investigating the safety and pharmacokinetics [what happens to a molecule when it is consumed] of PA supplementation is currently lacking. Although no side effects have been reported, safety data has not been collected alongside long-term supplementation.

That said, women suffering from the painful uterine condition endometriosis, or who may be prone to it, may want to avoid supplementing with PA. Research has shown that PA levels are significantly elevated in women with endometriosis, which may be for a number of reasons, including downregulation or upregulation of certain enzymes. But avoiding this supplement at that time is probably prudent.[13]

How should I take it?

Want to test it out for yourself? The currently recommended dosage is 750 milligrams of PA daily. The studies showing positive effects provided 450 milligrams of PA 30 minutes prior to training and 300 milligrams of PA immediately following training. On rest days, 450 milligrams of PA can be taken early in the day, and 300 milligrams of PA can be taken later. Given that there may be some blunting of PA's effectiveness when taken with whey, it may be best to take it on an empty stomach and not with food.

References

- Gonzalez, A. M., Hoffman, J. R., Stout, J. R., Fukuda, D. H., & Willoughby, D. S. (2016). Intramuscular anabolic signaling and endocrine response following resistance exercise: implications for muscle hypertrophy. Sports Medicine, 46(5), 671-685.

- Hornberger, T. A., Chu, W. K., Mak, Y. W., Hsiung, J. W., Huang, S. A., & Chien, S. (2006). The role of phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid in the mechanical activation of mTOR signaling in skeletal muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(12), 4741-4746.

- Tanaka, T., Kassai, A., Ohmoto, M., Morito, K., Kashiwada, Y., Takaishi, Y., ... & Tokumura, A. (2012). Quantification of phosphatidic acid in foodstuffs using a thin-layer-chromatography-imaging technique. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 60(16), 4156-4161.

- Avila-Flores, A., Santos, T., Rincón, E., & Mérida, I. (2005). Modulation of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway by diacylglycerol kinase-produced phosphatidic acid. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 280(11), 10091-10099.

- Joy, J. M., Gundermann, D. M., Lowery, R. P., Jäger, R., McCleary, S. A., Purpura, M., ... & Wilson, J. M. (2014). Phosphatidic acid enhances mTOR signaling and resistance exercise induced hypertrophy. Nutrition & Metabolism, 11(1), 29.

- You, J. S., Lincoln, H. C., Kim, C. R., Frey, J. W., Goodman, C. A., Zhong, X. P., & Hornberger, T. A. (2014). The role of diacylglycerol kinase ζ and phosphatidic acid in the mechanical activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling and skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(3), 1551-1563.

- Mobley, C. B., Hornberger, T. A., Fox, C. D., Healy, J. C., Ferguson, B. S., Lowery, R. P., ... & Wilson, J. M. (2015). Effects of oral phosphatidic acid feeding with or without whey protein on muscle protein synthesis and anabolic signaling in rodent skeletal muscle. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 12(1), 32.

- Hoffman, J. R., Stout, J. R., Williams, D. R., Wells, A. J., Fragala, M. S., Mangine, G. T., ... & Purpura, M. (2012). Efficacy of phosphatidic acid ingestion on lean body mass, muscle thickness and strength gains in resistance-trained men. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 9(1), 47.

- Escalante, G., Alencar, M., Haddock, B., & Harvey, P. (2016). The effects of phosphatidic acid supplementation on strength, body composition, muscular endurance, power, agility, and vertical jump in resistance trained men. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 13(1), 24.

- Andre, T. L., Gann, J. J., McKinley-Barnard, S. K., Song, J. J., & Willoughby, D. S. (2016). Eight weeks of phosphatidic acid supplementation in conjunction with resistance training does not differentially affect body composition and muscle strength in resistance-trained men. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 15(3), 532.

- Gonzalez, A. M., Sell, K. M., Ghigiarelli, J. J., Kelly, C. F., Shone, E. W., Accetta, M. R., ... & Mangine, G. T. (2017). Effects of phosphatidic acid supplementation on muscle thickness and strength in resistance-trained men. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 42(4), 443-448.

- Bond, P. (2017). Phosphatidic acid: biosynthesis, pharmacokinetics, mechanisms of action and effect on strength and body composition in resistance-trained individuals. Nutrition & Metabolism, 14(1), 12.

- Li, J., Gao, Y., Guan, L., Zhang, H., Sun, J., Gong, X., ... & Bi, H. (2018). Discovery of phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylserine as biomarkers for early diagnosis of endometriosis. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 14.