Squats can be bad for your knees. Period. But they're good for everything else.

So good, in fact, that you must do them. I don't care if you're a bodybuilder, a powerlifter or a ballerina. Ya gotta do them! The question is, how? The answer is, as safely as possible without losing any of the benefits! Sorta like drugs, no? The art and science of medicine dictates that while using drugs, you must minimize the risks while maximizing the benefits.

If there's one way to take your iron pill, then, it's in large doses! That means squatting!

In sports, knee problems are high unto a way of life, but squatting isn't the primary culprit. Among bodybuilders who have knee problems, however, squatting is the only culprit. In both cases, squatting properly can reduce, prevent or ameliorate many, many of the common knee problems inherent in sports. That they will make you a better bodybuilder or athlete is an unquestioned fact.

Speaking of the world of medicine and the practitioners thereof, you'll find precious few who have any real, first-hand knowledge of squatting technique or its effects (good and bad) on the knees. One who does is three-time California powerlifting champion Dr. Sal Arria, my fellow co-founder of the International Sports Sciences Association.

Dr. Arria, in the ISSA's course text, Fitness: Complete Guide for personal fitness trainers, listed many common knee problems and ways to prevent them. I've drawn heavily from that text in writing this article. I also drew from several other sources.

Knee Anatomy And Action

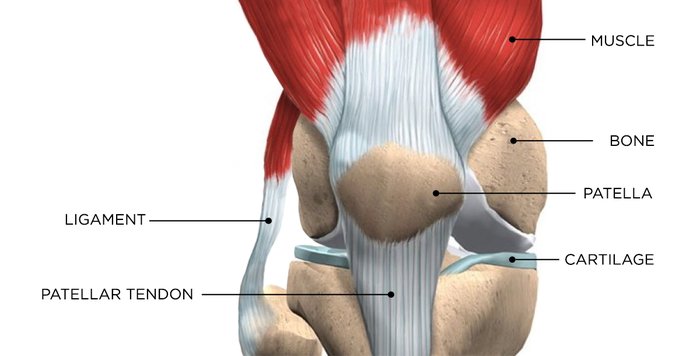

Keeping your knees healthy and asymptomatic begins with developing a functional understanding of how this unique joint is constructed (anatomy) and how it does and doesn't function (biomechanics).

The knee is a hinge-type joint, roughly equivalent to a door hinge, but with a little "twist" to lock it into full extension. Instead of a fixed axis (such as a door hinge has), however, it's a complicated movement consisting of gliding and rotation in such a fashion that the articulating surfaces are always changing. Hence, the axis is always changing. That can lead to trouble, particularly during unweighted exercises such as leg extensions.

It's almost a law that your quads and hammies should be of approximately equal strength in order to provide "balanced" development. Some experts claim that a ham-to-quad strength ratio of 1 to 1 reduces shear and hamstring pulls. At best, this is mere speculation. When I was a powerlifter, my hamstrings were close to twice or three times the strength of my quads.

To keep your knees healthy, develop a functional understanding of the joint anatomy and function.

Most sprinters are much stronger in the hammie department too, because that's what they all use! If you give attention to muscle balance, beware that speculation is rampant.

Seven different types of tissue comprise the knee - bones, ligaments, tendons, muscles, synovial fluid (bursa), adipose tissue and articular cartilage.

1. Bone: The bony structures forming the knee joint are the femur, tibia, and the patella.

2. Ligaments: Fibrous connective tissue which connects bone to bone, providing stability and integrity to the joint. The knee's ligaments are divided into two groups, eight interior and six external ligaments.

3. Muscle: We all have a clear idea as to what muscles are. Clearly, there are no muscles in the knee joint itself. The ones which act upon the knee joint are all external to the knee. They are listed below:

- The quadriceps, the muscles of the anterior (front) thigh.

- Next are the hamstrings, or the leg biceps, located on the posterior thigh.

- The other muscles of the knee all contribute to knee flexion and some toinward rotation.

4. Tendons: Fibrous bands that that connect the muscles listed above to their bony attachments. The knee's four extensors form a common tendon of insertion called the quadriceps tendon, which connects to the patella, and (below it) the patellar tendon to the tibial tuberosity.

5. Bursa: A bursa is a pad-like sac or cavity found near areas subject to friction, i.e. joints, particularly those located between bony prominences and muscle or tendon. It is lined with synovial membrane and contains synovia. There are twelve such sacs in the knee.

6. Adipose Tissue: For padding.

7. Articular Cartilage: Cartilage is the connective tissue which provides for a smooth articulation between the bones which form the joint. Cartilage also acts as a shock absorber. The two semi-lunar shaped menisci are the knee's only two cartilages. Located on the tibial plateau, they cradle the femoral condyles, or the rounded knobs of the lower femur. Since the tibial plateau is flat, and the femoral condyle is rounded, these two menisci (along with the bursa sacs) provide a better "fit" between these two bony structures.

The Gear Of Squatters

Two pieces of standard squatting gear—your shoes and knee wraps—should be carefully selected and used, not only to maximize both the short- and long-term health of your knees.

Shoes

Your shoes are literally where the rubber hits the road. Think of your shoes as the foundation of your leg training sessions. Wearing old or broken down fitness shoes for heavy squatting is like putting old, worn-out tires on a race car! There are several reasons to avoid training in your "tennies."

First, most general purpose fitness shoes simply lack adequate longitudinal or transverse stability, and have little or no arch support for heavy lifting. As you squat, your feet may develop a tendency to pronate, or "cave in" toward the inner side. When this happens, the knees are also forced inward, leading to a constant strain on the medial collateral ligaments, excessive shear force on the meniscus, and improper patellar tracking, which in turn can lead to chondromalacia.

If your feet tend to pronate anyway, or if you're prone to being "knock kneed" (and these two conditions are often associated with one another), it becomes even more important to select good training shoes.

Another important reason for using specialized shoes for squatting is that they provide a deep and solid heel cup, which prevents the foot from rocking and rolling to the outside, causing great stress on the lateral collateral ligaments of your knees.

Finally, there is a difference between a shoe being worn out and being broken down. Even if your shoes look fine, they still may offer no arch or heel support at all, either because they never had any to start with, or because after months of use, the supports have compressed to the point to where they no longer function as they were intended.

Think about it—a tennis shoe is meant to support a 160-pound tennis player, not a 600-pound squat! Loads like these cause the shoe to break down without visual signs of wearing out.

Knee Wraps

Knee wraps have long been a mainstay for competitive powerlifters, and for good reason. When properly used, wraps can dramatically improve knee safety during heavy squatting. More important, however, is the fact that wraps give you at least a 5-10 percent increase in how much you can lift. But there's a downside to using wraps also.

Wearing them while squatting under 80-85 percent or so is counterproductive to providing adaptive overload to various tissues comprising the knee. Simply, the wrap absorbs the stress instead of the tissues, so they never get stronger.

Guidelines for wearing knee wraps during squatting are as follows:

- Keeping your knees warm (wrapped loosely) improves blood flow and tissue elasticity.

- If the weight you're using is greater than 80-85 percent of your maximum, or

- If you have knee problems that require wearing wraps.

If you still insist on using them, go ahead and do so, but with the following points in mind. When buying knee wraps, opt for the ones that 1) weigh the most (more fabric equals greater protection, and 2) that stretch out to at least 19-20 feet in length (more times around the knee equals greater protection).

Do not purchase wraps that are bulky, heavily elasticized and stretch out to under fifteen feet. Tightness from elasticity does not afford you any real support!

Here are the steps to go through when putting your wraps on:

- Sit on a chair or bench. Begin with the wrap completely stretched and rolled up (this makes the process much easier than fighting to stretch the wrap as you go).

- With your leg straight, start applying the wrap below the knees, working upward. Wrapping from "in" to "out," (counterclockwise for the left leg, clockwise for the right -- this helps avoid improper patellar tracking), anchor the wrap by applying 2 layers below the knees, then move upward, overlapping each previous layer by one-half the width of the wrap.

- Apply the wrap tightly as you move past the knee, stopping somewhere on the lower third of the thigh (powerlifting rules allow 10 centimeters above the patella).

- Most of the wrap is wound around the leg just above the knee joint in orderto "pin" the quadriceps tendon to the femur below—better leverage). Tuck the end of the wrap under the previous layer to secure it. Repeat for the other leg.

An alternative more suitable for fitness and bodybuilding, perhaps, is to wrap tightly around the upper shin (where the patellar ligament attaches), then more loosely wound over the kneecap itself (this is important to avoid grinding the patella into the femoral condyle, creating a case of chondromalacia for yourself), then tightly wound over the lower quarter of the thigh.

Whenever you squat, hack squat, or leg press, your foot position is an important variable in determining not only the results you'll obtain from the exercise, but also the safety of your knee joints.

The rationale for wrapping the knees prior to heavy squatting is that it reduced the pulling forces on the lower quadriceps and the quadriceps tendon at it's attachment to the patella. This translates to significantly reduced chances of avulsing (detaching) your quadriceps tendon or tearing your quads during heavy squatting. The chances of your patellar tendon avulsing from your tibia are a bit less, but nonetheless omnipresent.

Stance Variables Affecting Knee Health

Whenever you squat, hack squat, or leg press, your foot position is an important variable in determining not only the results you'll obtain from the exercise, but also the safety of your knee joints. Although each individual must determine their own best stance exercise per exercise (based on their own anatomical peculiarities such as height and leg length), the following variables must be taken into consideration:

The quadriceps muscles can contract more efficiently when the feet are pointing slightly outward. They should never point straight ahead. If you squat with a very wide stance, your adductors tend to assist the quads. This can result in stress to the medial collateral ligament, abnormal cartilage loading, and improper patellar tracking.

During the descent phase of any type of squat, do not allow the knees to extend beyond your feet. The farther your knees travel over your feet, the greater the shearing forces on the patellar tendon and ligament.

Make sure that your knees point in the same direction your feet are pointing during the descent and ascent. Because of weak quads, many lifters inadvertently turn their knees inward during the ascent, placing great stress on the medial ligaments of the knee.

Although many top bodybuilders advocate a close stance for the purpose of isolating the outer quads, this is a myth, and it places you at risk, particularly since you'll have to use a lot of back to execute the lift, or (if you use heels) place great shear and compression on the knees. The best way to squat is to put your feet in a position where they can generate the greatest opposing force to the weight ("the athletic position").

Warm up thoroughly before squatting. Your muscles and other tissues of the knee joint love warmth! Remember the analogy, cold taffy breaks, warm taffy doesn't.

Maintain reasonable flexibility in the joints of your lower extremities and back. Many knee injuries can be traced back to poor position resulting from inflexibility.

Finally, be careful in the exit out of the rack, and getting "set" in the squat stance. After lifting the weight off of the pins, you should take just one step backward and immediately assume your squatting stance. This takes time to master, but eventually all the minute adjustments can be pared down substantially.

Once set in the stance, keep your feet "nailed down" for the duration of the set. Many people "fidget" with their feet and toes between reps which can cause a variety of problems ranging from a break in concentration to a loss of balance—and attendant stress on your knees.

Common Problems Of The Knee

Chondromalacia patellae: Softening of the articular cartilage of the patella that is produced by osteoarthritic degeneration. Such cartilage is unsuited for the high compressive loads and frictional forces involved in squatting, and roughening of the underside of the kneecap is common.

Tight quads are responsible for 80% of chondromalacia. Other causes include aging, repetitive overuse, and faulty biomechanics due to genetics.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS): Exemplified by pain in front of patella, which intensifies during activity. Also, pain during extended sitting, and/or walking up stairs. PFPS is further characterized by crepitus (noise), without instability.

PFPS is considered to be a tracking problem of the patella, caused by an imbalance between the medial and lateral quadriceps. The damage to the underside of the patella is not unlike uneven tread wear in a car that needs the tires rotated.

Unstable Knee Joint: Knee suddenly gives out. This is often caused by old injuries which have overstretched the knee ligaments.

Locked Knee: The usual cause of locked knees is a torn meniscus or a loose body within the joint capsule.

Swelling/Tightness: Nearly always indicates an internal injury. See physician immediately.

Crepitus: Noisy knees are no reason for concern, UNLESS accompanied by pain and/or swelling.